Part 2: Why MultiAgentic Systems Still Struggle to Turn Data into Actionable Insights

What’s missing between data, agents and decisions

Before You Continue

If you haven’t read Part 1, it is strongly recommend starting there first.

Part 1 walks through a concrete failure mode in modern agentic systems: How GenAI pipelines that look correct, modular, and well-designed still fail to produce decisions because context collapses at every handoff. It shows why adding more agents, better prompts, or richer tools doesn’t fix the problem.

Below article assumes that context.

What Part 2 Is (and Isn’t)

Part 2 is not about diagnosing the failure again.

It focuses on what changes when decision-making context is treated as first-class state and how letting decision traces flow across agents turns isolated intelligence into a coherent, decision-capable system.

In this part, we show how to move from siloed agent outputs to:

Shared reasoning state and

Capture decision traces that naturally accumulate in a form what industry calls as Context Graph in motion

Not as a theoretical construct but as a practical design pattern you can implement.

Why This Matters Now

In recent writing, several industry experts have started naming the same gap from different angles.

Inference by Sequoia notes in The Agent Economy article, that maintaining coherent context across multi-agent systems is hard. This is not because of missing intelligence, but because context fragments across agents, steps, and tools. That fragmentation is exactly what prevents insights from turning into decisions.

Ashu Garg makes the next critical distinction here: Context that agents actually need is not just data or rules, but context graphs as a layer that captures decision traces that never make it into systems of record, yet quietly run the enterprise.

His opinion is a bold one:

What Sequoia identifies as context fragmentation, and what Ashu Garg names as missing decision traces, are two views of the same gap: the absence of a system that can carry decision-making context end-to-end.

That framing resonates, but it immediately points to a harder question.

The Hard Question

How do you actually capture decisions/reasoning that makes data actionable?

This is non-trivial because:

Real systems aren’t fully observable

There’s no universal ontology

The world you’re modeling i.e., decisions is constantly changing

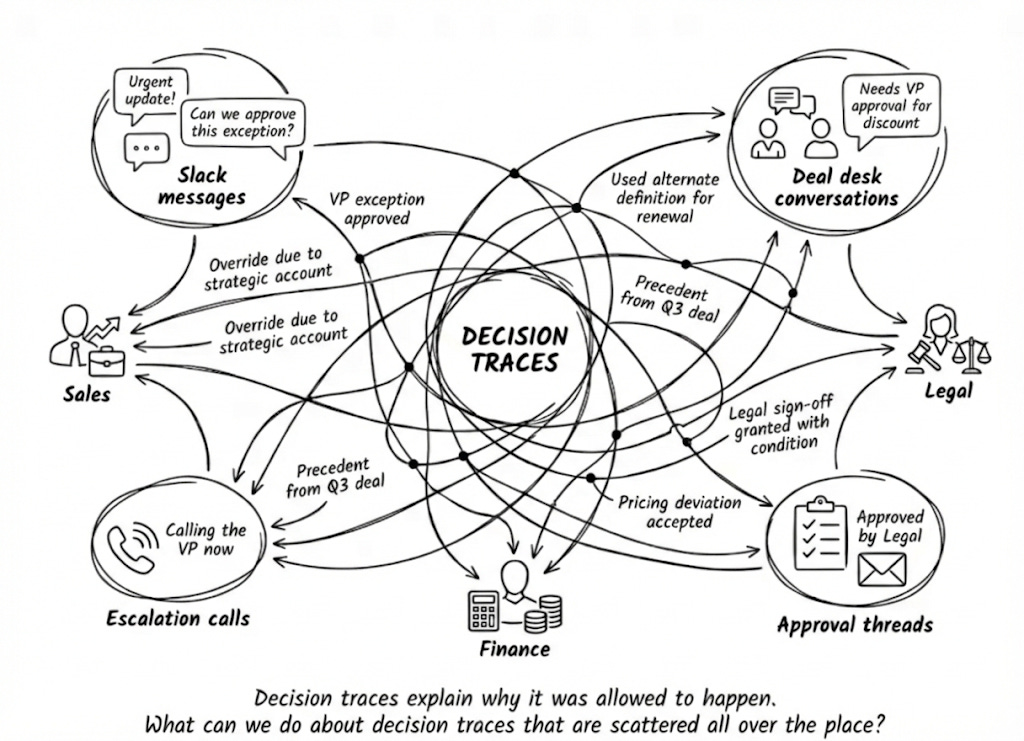

It needs tracking decisions that live in slack threads, Deal Conversations, Escalation calls and people’s heads.

Our Angle in Part 2

In Part 2, we approach this problem from a different, more operational angle.

Instead of asking how do we model everything, we ask a narrower question:

Given the decisions we’re already making today, within our realm of capturing possibility, can we let those decisions create global coherence across an AI pipeline?

In other words:

What if decision traces didn’t live in Slack threads and people’s heads?

What if they flowed through the agents already in the system?

What if context graphs weren’t built upfront but emerged as agents worked together?

That’s what we are going to demonstrate.

Not a theoretical context graph but a practical one, formed by letting user’s intent, agent’s assumptions, and trade-offs to persist as shared reasoning state across agents.

Let’s walks through the same SDR Analysis pipeline experiment that we saw in Part1, and see what happens if we track decisions that agents are making.

Solution2: SDR Analysis Pipeline

Context As Reasoning State (The Fix)

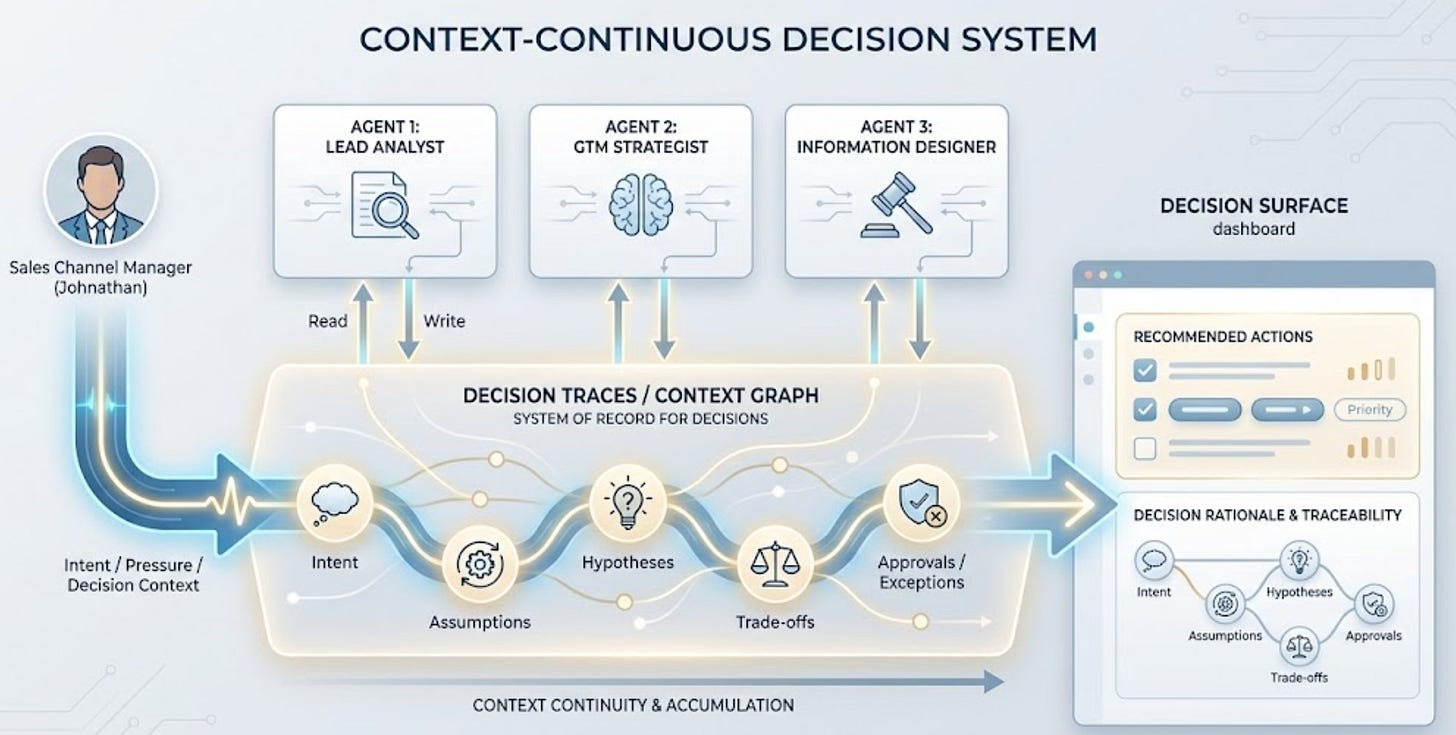

SDR Pipeline is using the same 3 agents as in Solution1 i.e., Lead Analyst, GTM Strategist, Information Designer but changed the most important thing in the system: how context behaved between them.

Instead of resetting the understanding gathered at each step, Solution 2 treated context as a shared, evolving reasoning state that persisted across the pipeline. Each agent no longer operated on a static handoff, but on accumulated understanding.

As a result of this new design, the workflow shifted away from pure task execution. It no longer began with abstract analysis in isolation, but with a concrete decision scenario, anchored in a real decision-maker (Johnathan) operating under real constraints.

Let’s see how that played out.

Step 0: The Glue: Introducing “Johnathan Bailey” Persona

Pipeline context is initialised. We injected current user asking the question as a persona into the system:

“Johnathan Bailey, a newly promoted Sales Channel Manager. He is under pressure, learning fast, and reports to leadership that expects answers, not analysis theatre.”

This context is not decoration. It fundamentally constrained how agents in the pipeline are expected to reason/analyse (details below).

Step 1: The Lead Analyst Agent

Context Enters: As Johnathan Persona

Input Question:

“Identify ‘Technology’ sales in the ‘Central’ region are driving the loss.”

Output (Instead of a neutral exploratory response, agent spoke directly to Johnathan’s situation):

“Johnathan, I understand the pressure you’re under from the VP regarding the Central Region’s profitability. Let’s dive into the data to pinpoint the issues…”

This framing clearly constrained the analysis.

The agent is no longer exploring what’s interesting.

It is answering what Johnathan needs to defend in front of leadership.

Analysis converged quickly:

“Identified specific products within the Technology category in the Central region that are either operating at a loss or generating very low profit margins, dragging down the overall profitability… cost to sell (including discounts and shipping) is higher than the revenue generated…”

Handoff to next Agent: Crucially, the agent did not collapse this into a static summary. It ended with a set of commitments passed to the next agent:

“To provide a more comprehensive report to your VP, we should:

– Deep Dive into Loss-Making Products

Investigate their pricing, discount levels, shipping costs, and unit costs.

– Review Discount Strategies

For loss-making products like the SanDisk card, the discounts might be too aggressive

– Identify High-Volume, Low-Profit Items

Are there other Technology products in the Central region that sell in high volumes

but have profit margins similar to the Anker Astro charger?

– Compare with Other Regions/Categories

To identify if this is a regional-specific issue or a broader product line challenge.”

This is the first critical shift.

The output is not an answer.

It is a set of commitments handed to the next step.

Step 2: The GTM Strategist Agent

Context Evolves:

The GTM Strategist did not just receive a data table unlike in Phase1. It received Johnathan’s persona, the Analyst’s hypotheses, and the unresolved questions to act.

Input Question:

Define the “So What” for the identified profitability issues for Johnathan.

Output: Context-Aware Framing

The agent responded directly to Johnathan’s role and pressure:

“This isn’t a statistical blip. The profitability decline in the Central Region, especially in Technology, is a direct drain on P&L, limits regional growth, and demands immediate intervention.”

From the first line, the response anchored the analysis in P&L ownership,

execution risk, and leadership accountability.

Analysis: Turning Findings into Decision-Relevant Meaning

The agent articulated why the findings matter, referencing specific SKUs and translating them into concrete business risk and opportunity:

Direct financial loss (Negative ROI):

Loss-making products like the SanDisk Ultra 64GB MicroSD card generate a $10.79 loss per unit at a 20% discount, directly eroding regional profit and masking true performance.Fragile margins (High risk, low return):

Products like the Anker Astro 15000mAh charger operate at 4% margin without discounts, making the P&L extremely sensitive to even minor cost or pricing changes.Sales opportunity cost:

Time spent selling loss-making or razor-thin margin products displaces effort from genuinely profitable opportunities, reducing overall sales ROI and quota efficiency.Strategic discounting failure:

Discounts are being applied without profitability thresholds, turning pricing into an uncontrolled lever that accelerates margin erosion and sets poor customer precedents.

Each point translated data into action pressure: pricing intervention, SKU review, discount policy tightening, and targeted customer strategy.

Handoff to next Agent: Before moving on, this agent passed a clear directive forward, turning a business problem into a design constraint:

“ To effectively communicate these critical insights and empower Johnathan with actionable intelligence, dashboard must visually emphasise the following strategic themes and narrative points…”

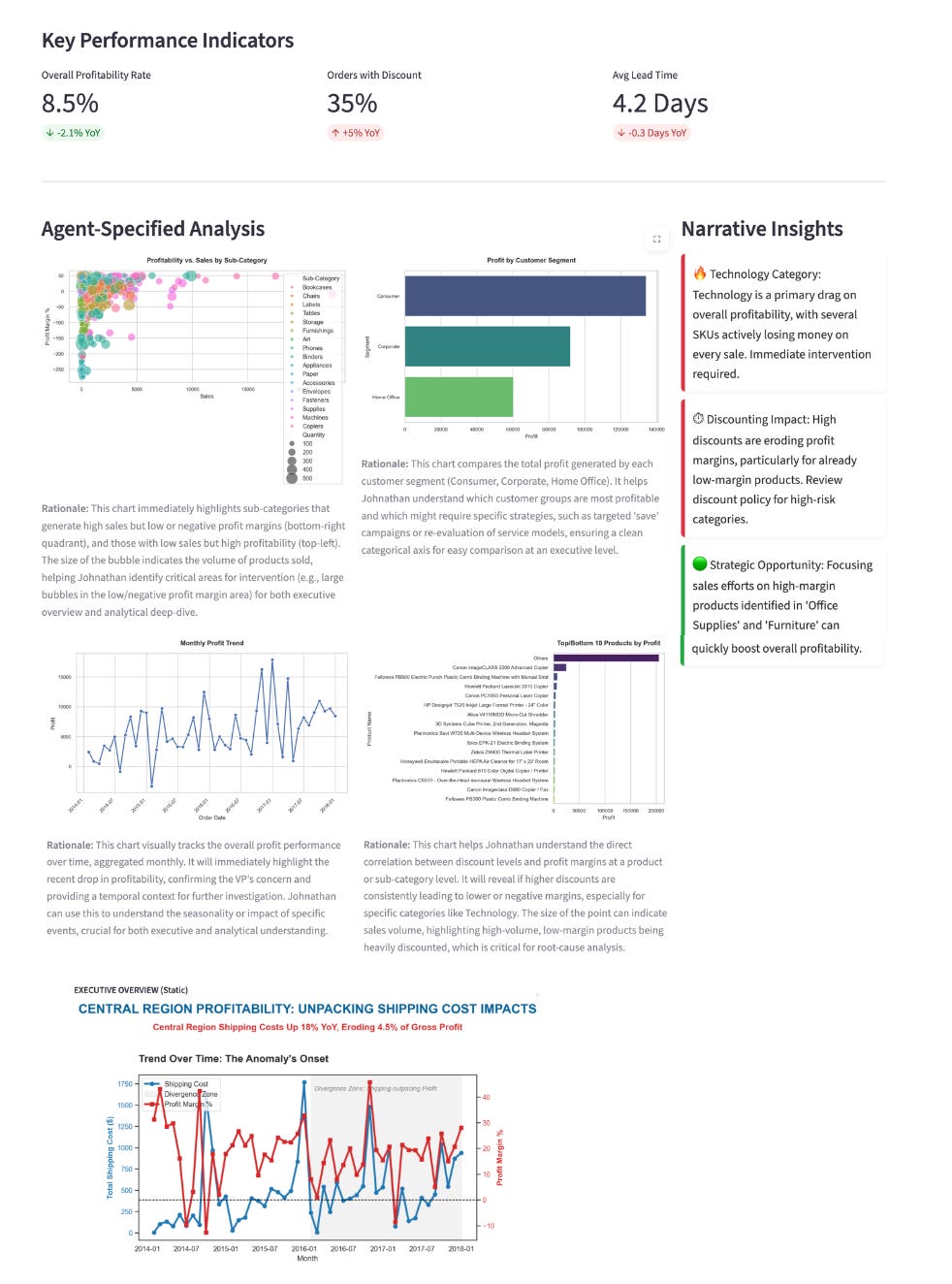

Step 3: The Information Designer

Context Solidifies: Context becomes Structure

By the time the Information Designer entered, they were not designing in the dark. They knew who Johnathan was, why the VP was asking questions, and which hypotheses (discounts/shipping) mattered.

Output:

“Johnathan, this dashboard is designed to provide with both an executive overview and the analytical depth needed to address the urgent profitability drop…”

Analysis:

Every design choice tied back to prior reasoning:

KPIs reframed around drivers, not summaries

Instead of generic metrics like Total Sales or Average Profit, the system elevated the factors that actually mattered: Discounts and Shipping Costs.Trend Charts: Showed exactly when the anomaly began.

Sub-Category Views: Isolated “Accessories” vs “Phones” (answering the Analyst’s hypothesis).

Built-in rationale for action

Every chart included guidance on how Johnathan should use it, what to investigate, what to prioritise, and where to act.Root causes made explicit: Narrative Insights called out “critical profit drains” rather than generic summaries.

Dashboard: The resulting artifact was no longer a reporting dashboard in the traditional sense. It was decision surface

Missing Layer surfaced by this Experiment:

Decision Traces Captured as Context Graph

What this experiment revealed was not just a better way to design dashboards or orchestrate agents. It surfaced a missing architectural layer, one that explains why most agentic systems struggle to operate in the execution path and drive decisions.

To see it clearly, it helps to map the experiment back to how enterprises are built today.

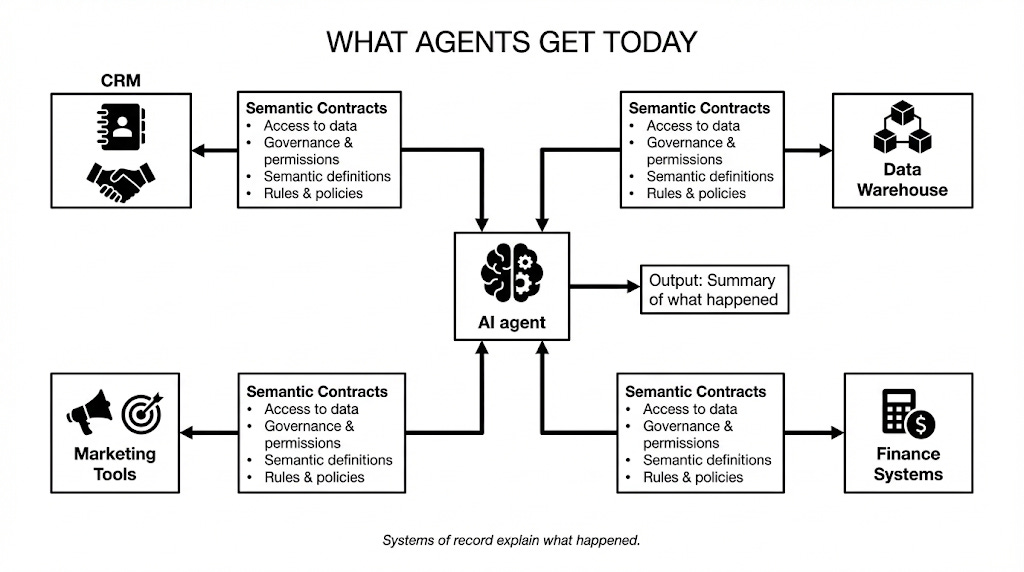

What Agents get today: Systems of Record and Rules

As Jamin Ball notes in Long Live Systems of Record, enterprises have spent decades building systems of record by centralising data from different domains, metrics and business entities. Data Agents, that are inherently cross-system, get access to such data, rules that govern it, relevant access policies and semantic contracts that determine which rule wins for which purpose.

Solution1 of our experiment operated entirely within this model.

Agents had access to data and rules that helped it produce correct artifacts i.e., tables and summaries of what happened in the past. But the system could could not drive decisions.

Missing Layer of Decision Traces

However, Systems of Record and Rules are only half the picture. The other half is decision traces because enterprises do not actually run on data definitions alone. They run on decision traces.

Solution2 implicitly reconstructed this combined picture. It showed how agents can move beyond simply accessing data or applying rules to preserving decision-making context as the system progresses.

What this blog refers to as context continuity is, in effect, the sustained flow of decision traces across agents and pipeline steps. Solution1 failed because the system only passed artifacts forward, severing the link between data and judgment. Solution2 worked because decision traces i.e., user intent, reasoning, and business purpose remained alive throughout the pipeline.

Combined Picture: System of Records + Rules + Decision Traces

It is now clear that for agents to be truly cross-system, action-oriented, and capable of driving decisions, they must be grounded in two complementary layers:

Systems of Record and Rules: capturing what the data says and what should happen in general.

Systems of Decision Traces: represented as context graphs that preserve how decisions were actually made in specific situations.

This is the difference between systems that report outcomes and systems that can own decisions.

Conclusion: Reimagining the Systems of Records to Drive Decisions

It’s time to rethink what a system of record means in an AI-driven enterprise to transition from AI that explains past into AI that shapes what’s next.

AI that shapes what happens next:

Most organizations are not lacking data.

They are lacking systems that remember how decisions are made.

The real shift comes from capturing the Decision Traces that make data actionable like the intent behind a question, the exceptions that were granted, and the precedents that turn data into action.

This blog showed how those traces can be made explicit and allowed to flow across agents, forming a continuous decision context rather than disconnected outputs. For this, organizations need to shift from stateless pipelines to context-continuous systems where context reasoning flows as it progresses from one agent to another. When these decision traces are preserved and connected, what industry describes as context graphs, AI systems move from mere reporting on the business to active participation in it.

According to Foundation Capital, this is an emerging opportunity.

The next trillion-dollar platforms won’t be built by:

Adding more intelligence to data (or) Making Agents Autonomous.

They’ll be built by owning the decision layer

(Systems of Record for How Decisions are made)